Hey everyone — it’s good to be back (finally)! I’ve mentioned before that many of my friends (along with my wonderfully patient wife, Glynis) keep reminding me that I don’t always need to have some big, fabulous thing to show in order to create a post here. While knowing they are right, I continue to struggle with feeling a lack of anything genuinely interesting to display or speak about … then the time between these updates grows longer and longer, and all my anxieties along with it. It’s a vicious circle I am (still) determined to break, even if that means sharing something that didn’t work right, or to express a hope/frustration in a line or two.

Hey everyone — it’s good to be back (finally)! I’ve mentioned before that many of my friends (along with my wonderfully patient wife, Glynis) keep reminding me that I don’t always need to have some big, fabulous thing to show in order to create a post here. While knowing they are right, I continue to struggle with feeling a lack of anything genuinely interesting to display or speak about … then the time between these updates grows longer and longer, and all my anxieties along with it. It’s a vicious circle I am (still) determined to break, even if that means sharing something that didn’t work right, or to express a hope/frustration in a line or two.

I hope your holiday celebrations were warm and wonderful, and that this year has been good for you thus far. With so much of the negative being emphasized in the world right now, it’s more important than ever to stay aware of the positive and be grateful for all that we have.

Like many of you, the grinding process of working towards long-range goals can make it easy to slip into self-recrimination, allowing devastating sentiments to cloud the precious creative drive we depend upon as artists. I discovered a welcome antidote for those pernicious feelings while reading an article by one of my favorite authors, Malcolm Gladwell. A celebrated contributor to The New Yorker, Mr. Gladwell has written several fascinating — and hugely successful –books (Outliers, The Tipping Point, Blink, and most recently David and Goliath) that each had a profound effect upon me, resulting in much reflection and a renewed sense of curiosity about how things may actually work (as opposed to how we sometimes, mistakenly, think they do); his TED talks are highly recommended as well.

In the article Late Bloomers, Gladwell begins with the story of a young, aspiring writer named Ben Fountain whose seemingly rapid ascent from obscurity to literary darling is revealed to have actually transpired over the space of eighteen years — most of it spent working away at his kitchen table.

Although the focus of the piece is to ask why we equate genius with precocity, I found great comfort in the way he describes two different artistic personality types.

First there is the prodigy, a fresh, young creator that just blows-up right from the start; in cinematic terms, think Orson Wells, who created his masterpiece Citizen Kane at twenty-five, or Steven Spielberg setting the world on fire with Jaws before even turning 30. Then there is the late bloomer, who takes a much longer and protracted time to develop their style and produce the works they would eventually become known for. A great example of the latter is Alfred Hitchcock, who made seven of his greatest films (including Rear Window, North by Northwest, and Psycho) between the age of fifty-four and sixty-one! (Insanity!)

Can you guess which side of the line I lean towards?

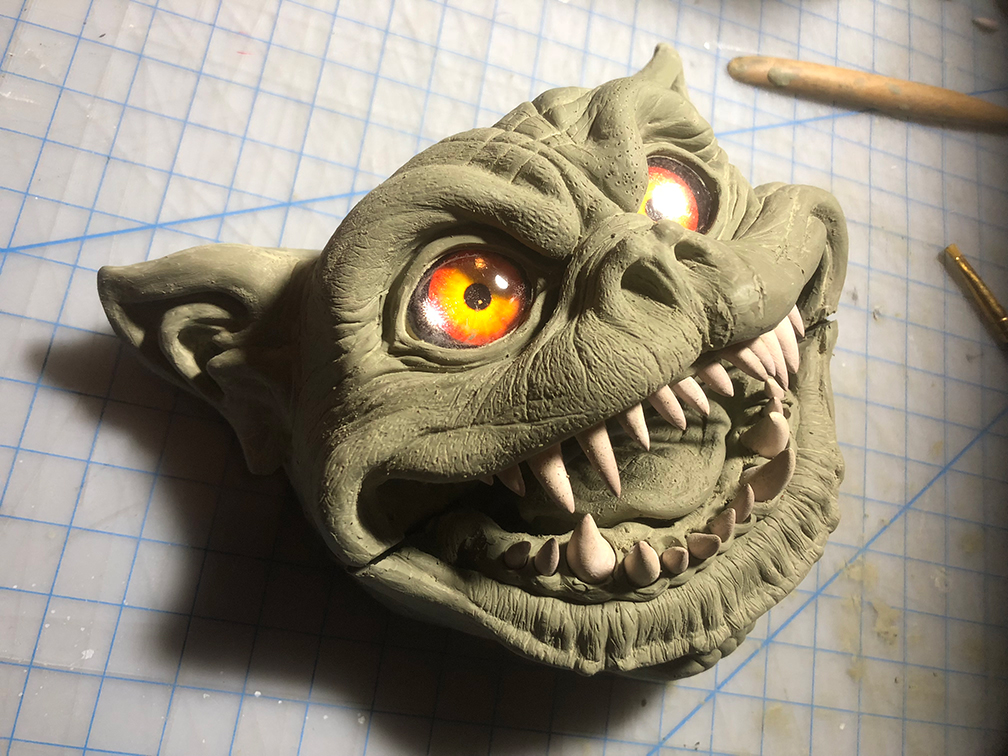

If you read the article, you’ll notice that many of these late bloomers continue to work on and refine their art throughout the lengthy process of its creation. And although some of the attributes he lists for this creative type don’t fit, I can identify all too well with this familiar methodology, and wanted to share an example from The Price to illustrate…

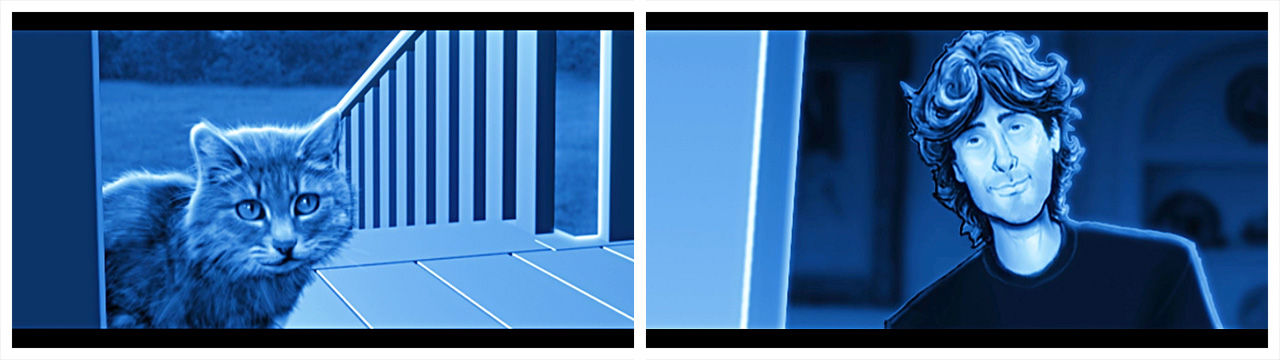

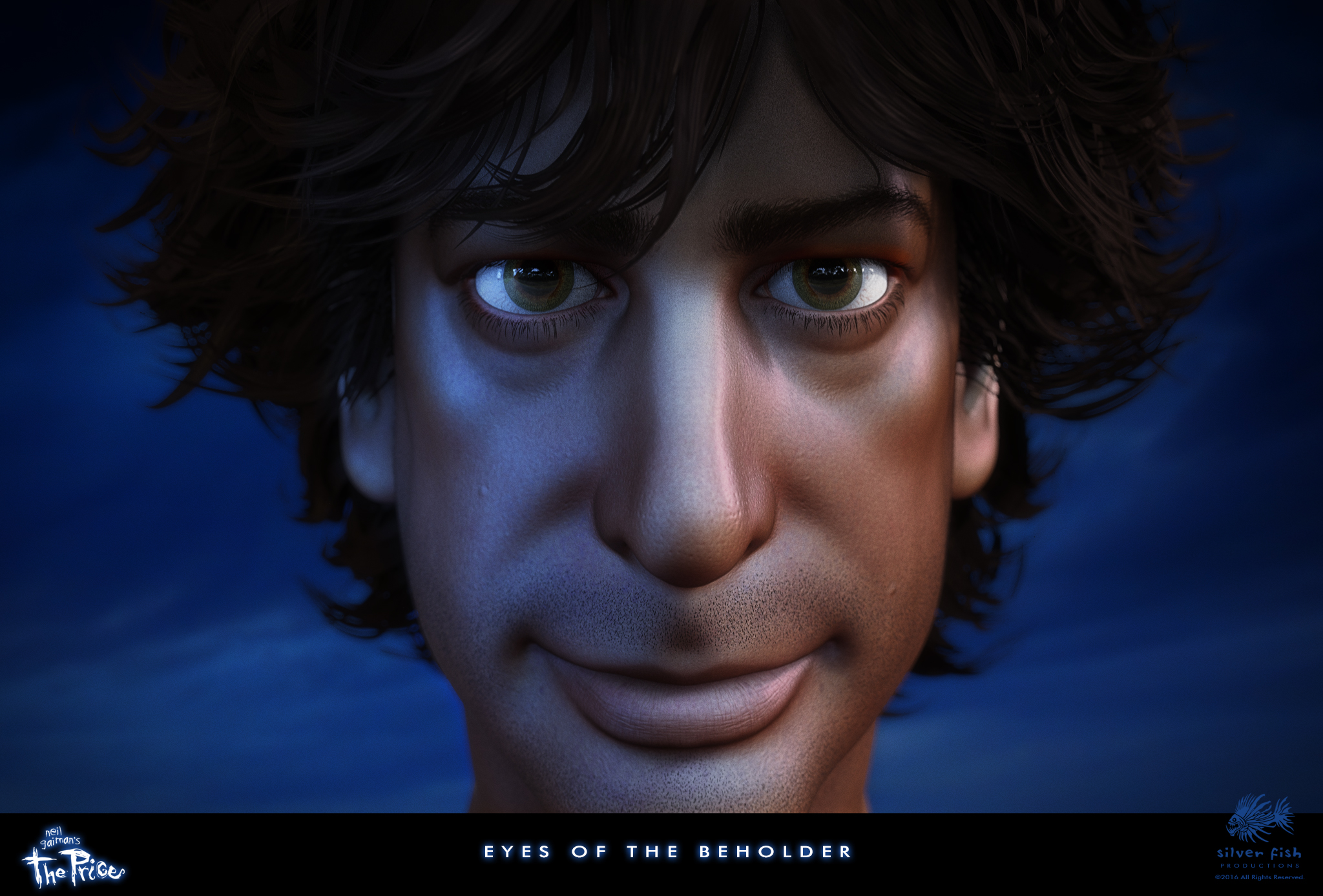

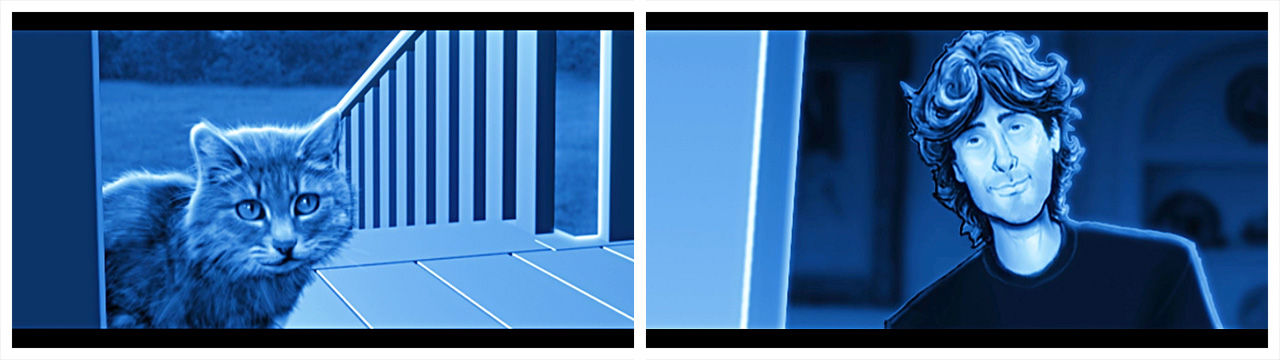

Near the beginning of the animatic (the simplified, rough-draft of the movie), I choose to introduce the audience to the narrator by having a stray cat approach the front door of his home. Using storyboard illustrations, this was accomplished with cuts between the feline visitor and the opening door.

In the actual film where the camera is free to move about the 3D ‘set,’ I devised a more immersive shot; we glide up the steps and across the porch, past the stray, and push-in close to look up at the door as it opens (a point-of-view similar to the cat’s). I was thrilled with the effectiveness of the move, but then noticed a glaring issue … the bricks looked fake!

To explain:

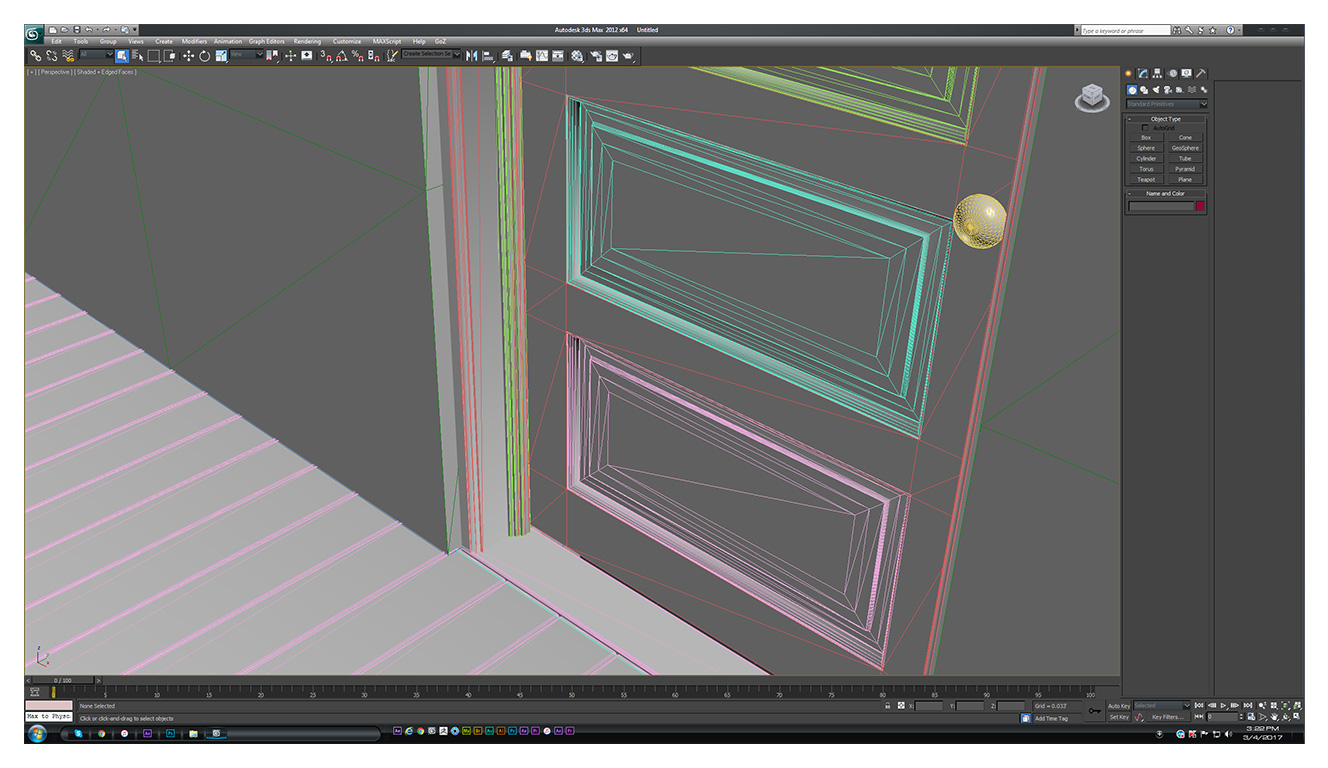

The model of the house was made with a minimal amount of polygons, the building blocks for 3D images. Simply put, the more polygons in a given object, the more complex and realistic it may look — but the computer has to work harder to ‘draw’ or render them onscreen. With limited computing power, that becomes a vital issue.

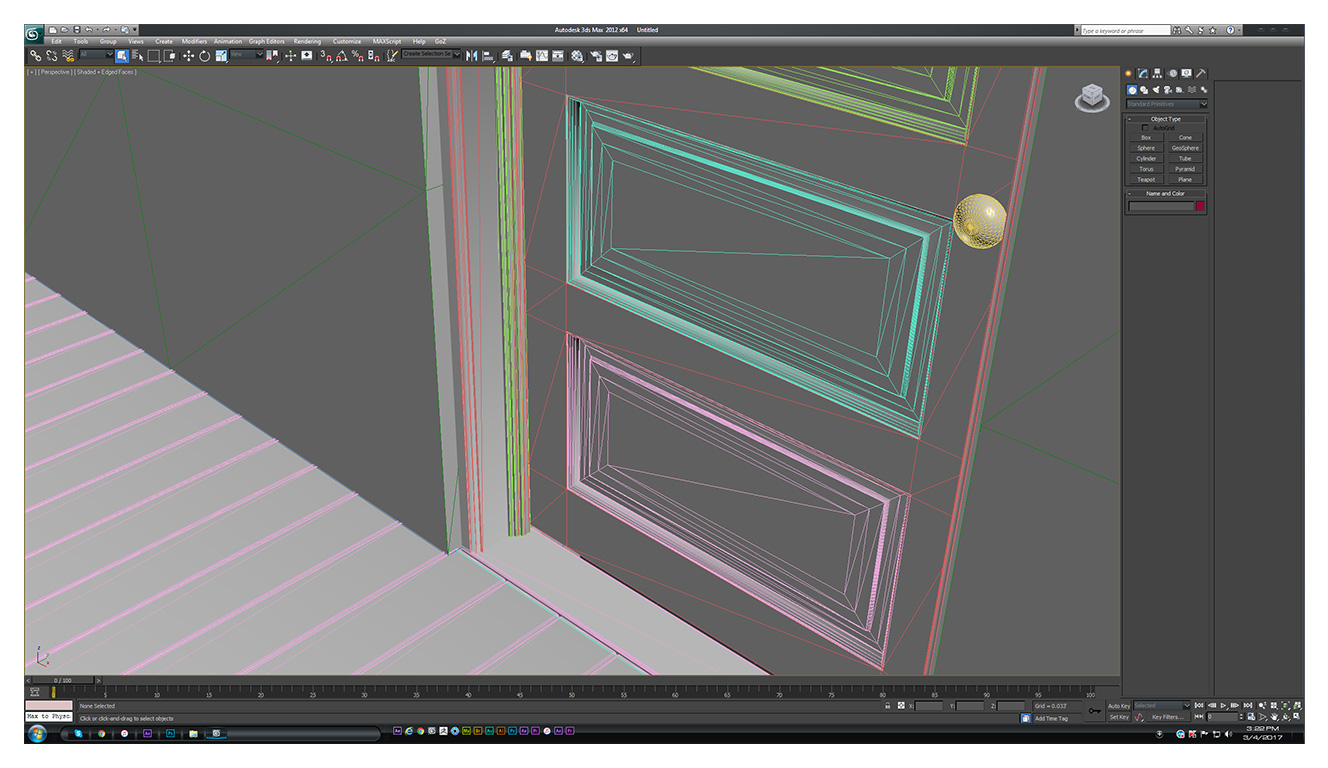

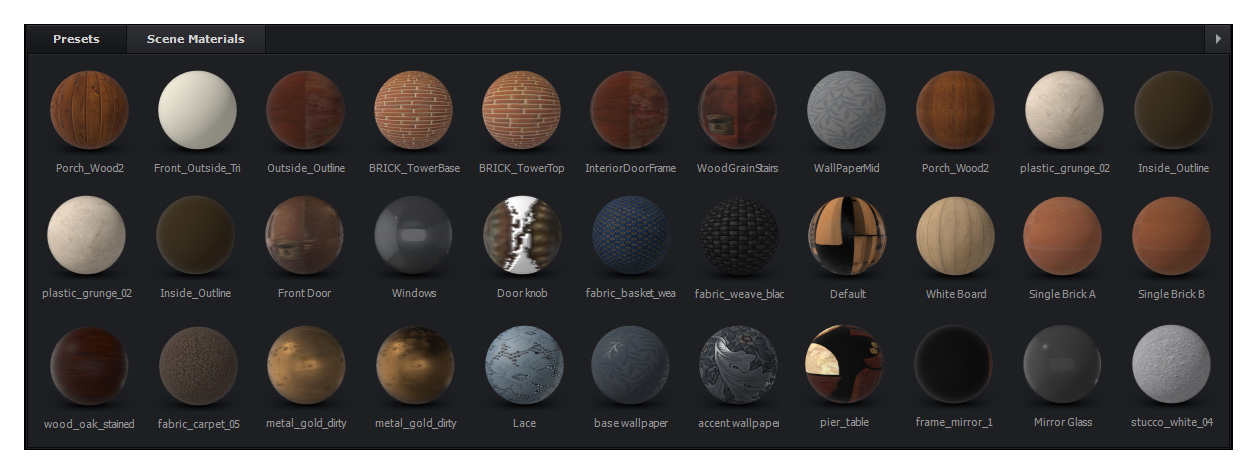

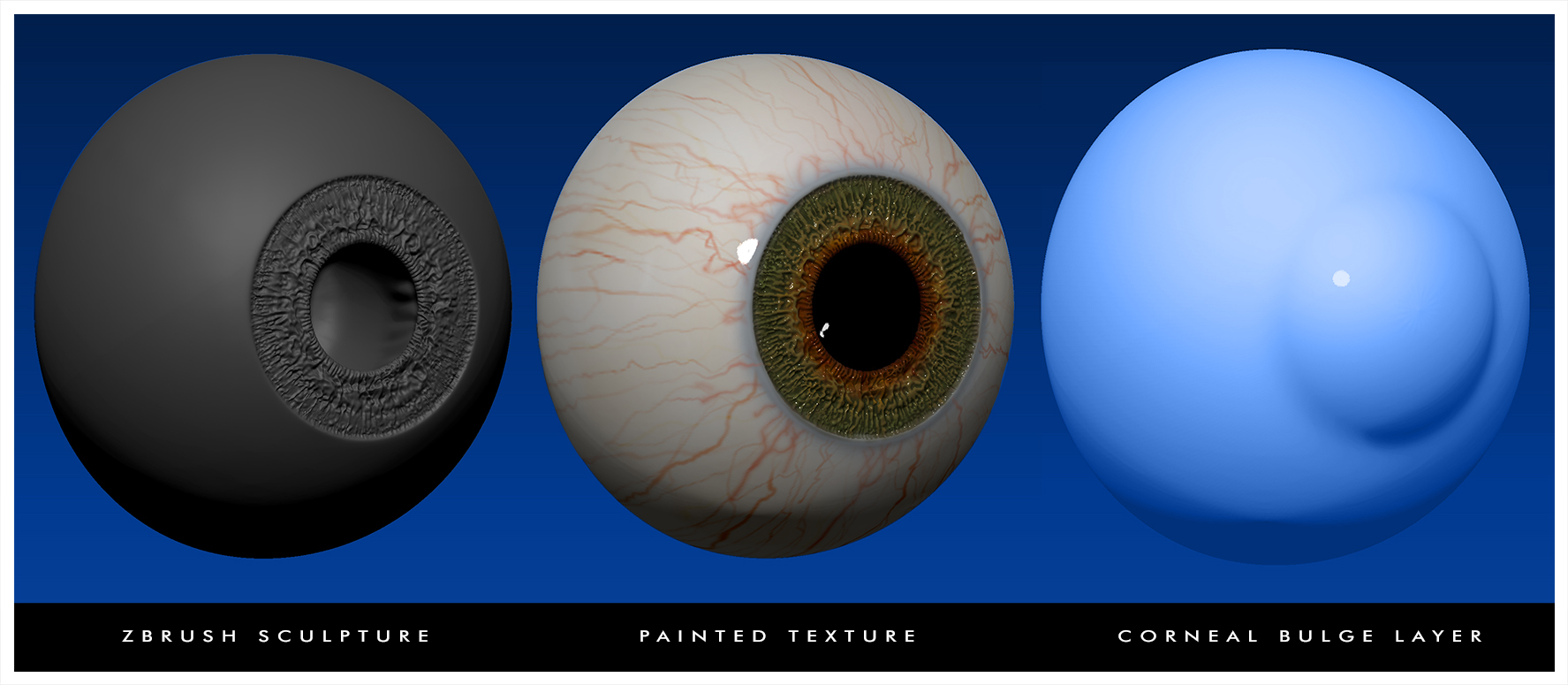

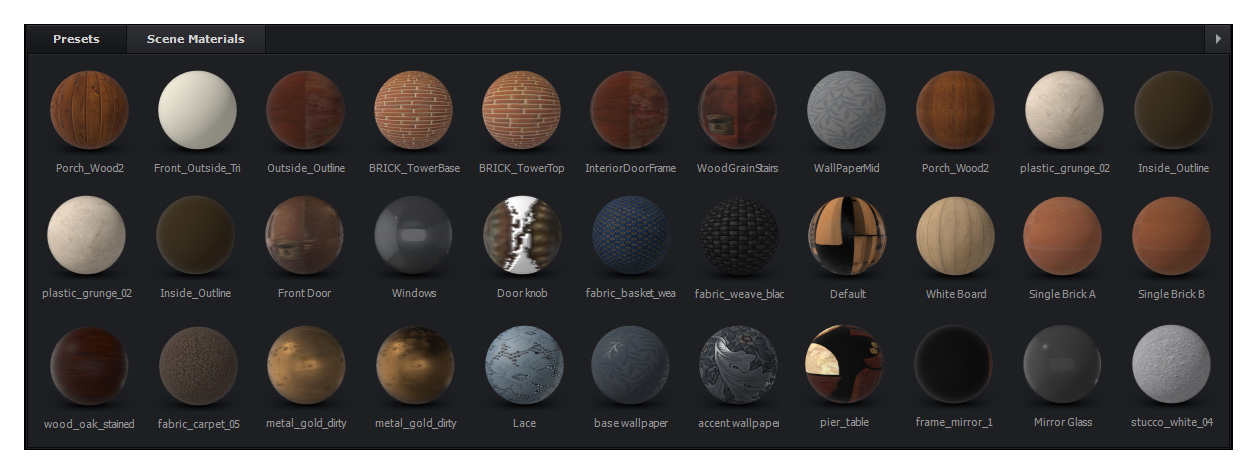

All of the brightly-colored lines in this image make up the triangular shapes of the polygons, and they act like the frame for the model of the front porch. These digital frames are covered with images called texture maps, using a technique similar to wallpapering. Below are examples of some of the textures used (many of which were made from photographs I took while visiting the legendary Castle Gaiman).

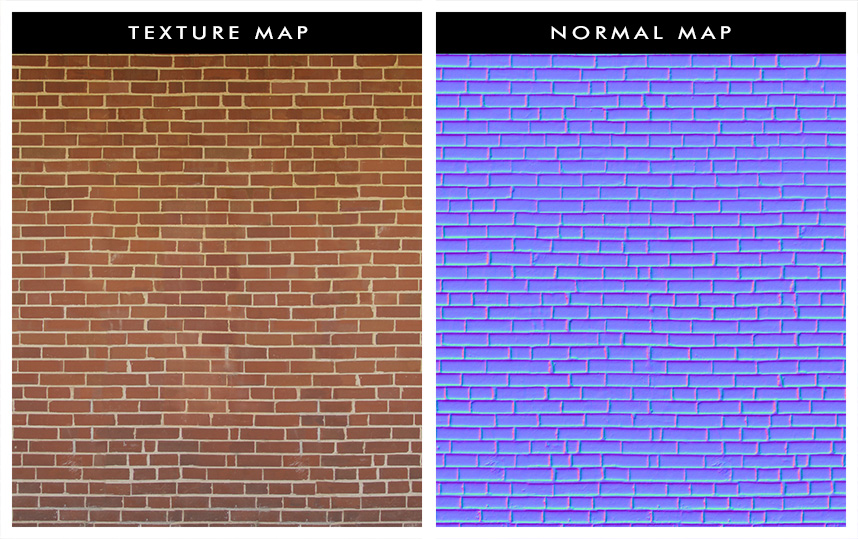

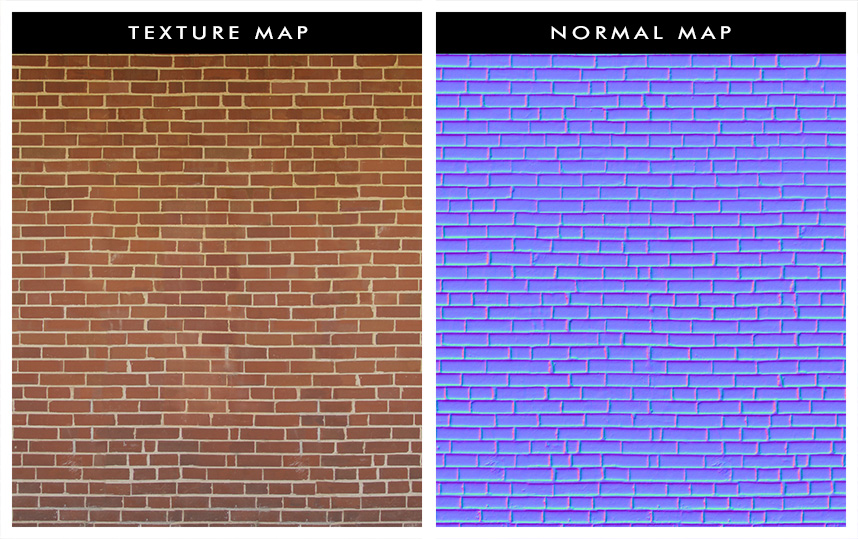

To keep the poly-budget down to a reasonable level that my computer won’t choke on, many details have to be ‘faked’ with texture maps and another type called a ‘normal’ map (the name doesn’t make any sense at first, but we aren’t going to go into that right now). The seemingly bizarre coloration of the normal map tells the computer how to light a flat object — like a smooth, featureless wall — so it looks like rough bricks with sunken grooves of mortar.

These two maps go a long way toward making it appear as though the house walls are actually made of bricks … until you get to the hard, sharp-edged corners … and the jig is up. Illusion shattered — it looks like wallpaper!

While that may not seem like a big deal, by having the camera move in this close, the lack of edge detail becomes extremely distracting! The whole point of the shot is to focus anticipation on seeing who is opening the door, not the limitations of my PC, right?

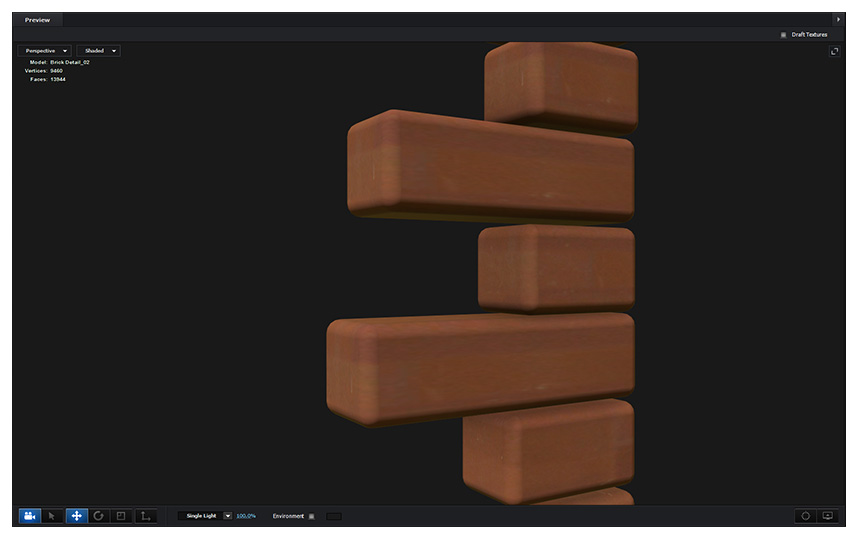

To go back and rebuild the porch walls with individually modeled (and textured) bricks would have been a huge, labor-intensive job, and defeat the purpose of keeping the assets lean in the first place, so … what to do?

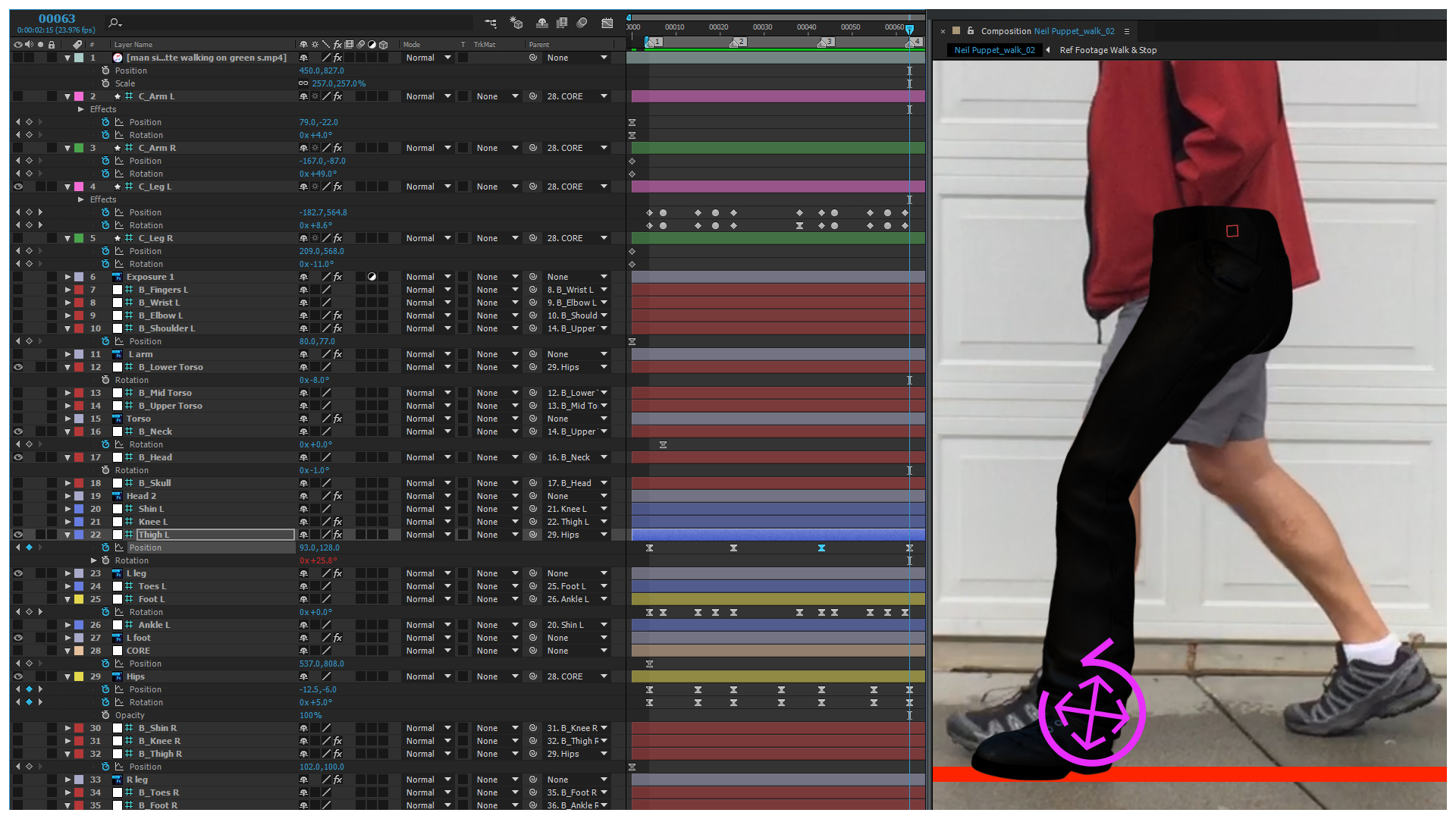

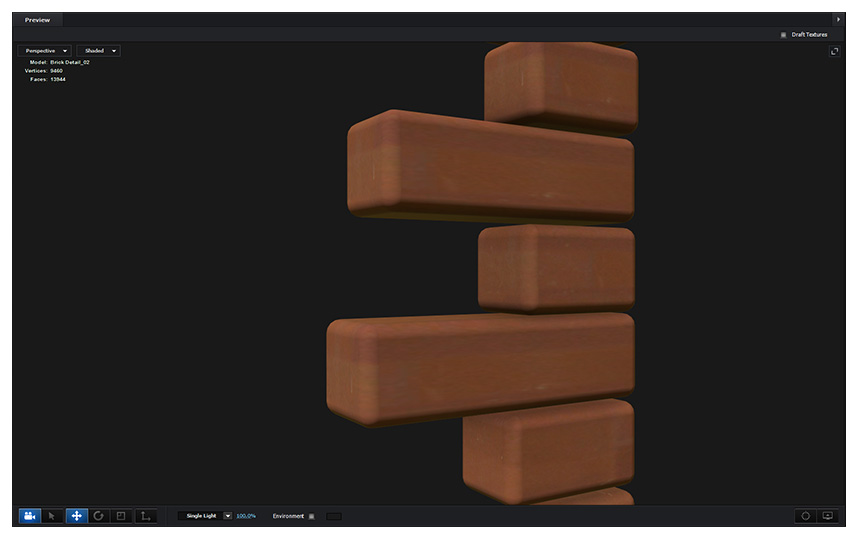

Using the Element 3D plugin for After Effects (which didn’t even exist when I started this project), I developed a way to build very low-poly bricks and insert them into the existing model only along the edges that were giving me trouble. Look at the difference with those bricks in place…

…and then without.

And in the final shot, those bricks even cast a shadow across the door, adding one more detail that helps keep the illusion onscreen alive.

Back to Late Bloomers, I could empathize with some of the artists Mr. Gladwell talks about (like the great French painter Cézanne), and was grateful to note that several of them endured adversities similar to my own. Here is a particularly uplifting passage:

“On the road to great achievement, the late bloomer will resemble a failure: while the late bloomer is revising and despairing and changing course and slashing canvases to ribbons after months or years, what he or she produces will look like the kind of thing produced by the artist who will never bloom at all. Prodigies are easy. They advertise their genius from the get-go. Late bloomers are hard. They require forbearance and blind faith.”

Gladwell then states the extremely vital role that patrons play in allowing these types of artists the time to be able to develop and produce their work.

“That word [patron] has a condescending edge to it today, because we think it far more appropriate for artists (and everyone else for that matter) to be supported by the marketplace. But the marketplace works only for people like … Picasso, whose talent was so blindingly obvious that an art dealer offered him a hundred-and-fifty-franc-a-month stipend the minute he got to Paris, at age twenty. If you are the type of creative mind that … has to experiment and learn by doing, you need someone to see you through the long and difficult time it takes for your art to reach its true level.”

That brings me to all of you, and the overwhelming surge of gratitude I feel towards everyone who has believed in my vision and generously supported this project, who continue to send so much encouragement and … yes, love.

“Late bloomers’ stories are invariably love stories, and this may be why we have such difficulty with them. We’d like to think that mundane matters like loyalty, steadfastness, and the willingness to keep writing checks to support what looks like failure have nothing to do with something as rarefied as genius. But sometimes genius is anything but rarefied; sometimes it’s just the thing that emerges after twenty years of working at your kitchen table.”

I can’t say it any better than that. My deepest thanks to everyone (beginning with Mr. Neil Gaiman, my family, and to each one of you) for allowing me to make this little film, to honor a story I fell in love with and can’t get out of my mind/heart until it can be shared with the world.

It’s been a long, cold winter, but spring is coming …